Abstract

It all began with Claudio Monteverdi, the most important Italian composer of the early 17th century: He made music theatrical. Lovers, loners, jealous hearts, and revenge-seekers alike appear on stage, lamenting their suffering, and turning their innermost thoughts into song. Before Monteverdi’s operas, singers had never appeared both realistically and heart-wrenchingly self-aware at one time. The same holds true of his books of madrigals, in which the polyphonic vocal art of the Renaissance gives way to the expressive power of the individual voice, set to music. Monteverdi labels his madrigals as genere rappresentativo, a performance style that encompasses both staging and gestural, dance-like movements. His eighth and final book of madrigals, published seven years before his death, is the most popular. It is a collection of works infused with the sum total of his stylistic development and sense of drama. Music from this Eighth Book of Madrigals is at the center of Christian Spuck’s new ballet production. Like its predecessors – Verdi’s Messa da Requiem or Schubert/Zenders Winterreise – it unites vocal soloists and the Ballett Zürich on stage.

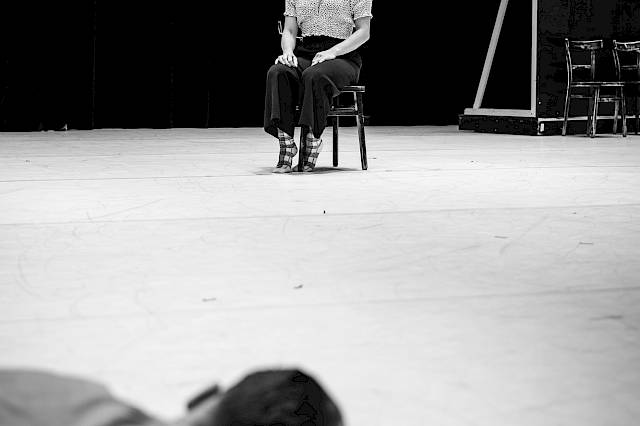

Engaging with Monteverdi means starting over from the beginning, exploring the magic of the origins of musical drama that blossoms in his arias, dance interludes, and madrigals. How can movement, a scene, or dance arise from the forlorn Lamento della Ninfa, one of Monteverdi’s best-known laments? What kind of choreographic expression is awoken by the trembling excitement of Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, which tells of the struggle facing a couple that oscillates between love and hate? Instead of looking for an all-encompassing story that spans Monteverdi’s miniature dramas, Christian Spuck draws energy from the power of fragmented and danced abstraction. In a space designed by designer Rufus Didwiszus, theater ends and begins anew.